This post under construction.

Updated 4 Dec 2024 - to be continued. I have been meaning to do this for a long time.

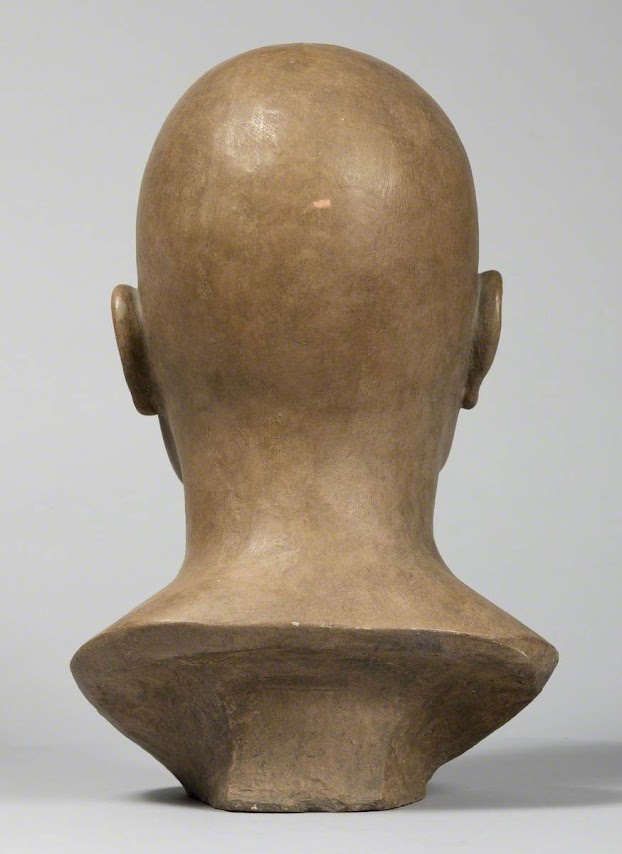

Bust of a Moor.

Attributed to Francis Harwood (1727 - 83).

Working in Italy mainly in Florence from 1752 until he died.

Patinated Plaster.

A Life Mask / Head and Upper Torso

Height 65 cms.

A recent discovery.

Sold by - Auctioneers Pandolfini Casa d'Aste, Florence. Italy.

Lot 101 on June 30, 2020.

https://www.pandolfini.it/uk/auction-0340/toscana-secolo-xviii-12020002941

Where is it now??

In the absence of any more high resolution photographs - it would appear that this bust is the prototype for the two busts below, but at this point I cannot be 100% sure - the scar on the forehead is not visible and there are real differences in the hair.

These differences in the hair can probably be accounted for because when making the plaster piece mould the sitters hair would have needed to be protected (probably by some sort of grease) in order to prevent the hair being caught in the setting plaster.

....................

What to me is plainly obvious is that this bust has been taken from life - the closed eyes suggest that a mould was created around the head and shoulders of the model and a cast then taken.

In order to make the marble busts the eyes would have had to be remodelled and carved but the bust and the rest of the head could be relatively easily transferred to the marble with the aid of a pointing machine.

It is my belief that Roubiliac would have used this method on more than one occasion.

Bust of a Black Man

c. 1758.

Black limestone (pietra di paragone) on a yellow Siena

marble socle.

Overall: 28 × 20 × 10 1/2 inches (71.1 × 50.8 × 26.7 cm

Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection

The centre website is rather vague on the provenance of this

remarkable bust.

Before Paul Mellon bought it in 1967, the Yale bust had been

part of the Esterhazy Collection in Vienna, where it was misattributed to the

Renaissance artist Alessandro Vittoria (1525–1608) and called “The Blackamoor”,

and in 2006 it became part of the Yale Center for British Art collection.

"This remarkable bust may be a portrait: details such as the

small scar on the man’s forehead and the subtle depressions in the skin around

his temples, nose, and eyes suggest close study of an individual sitter.

However, the sculptor Francis Harwood, who was based in Italy, specialized in

making copies of classical statues for sale to English Grand Tourists, and so

it is also possible that this is a copy or adaptation of an Antique model."

"A third possibility is that the bust was made as an

allegorical image of “Africa.” A passage from Joseph Baretti’s "Guide

through the Royal Academy" (London, 1781) suggests that, by 1781,

Harwood’s "Bust of a Man"—or something very similar—had entered the

cast and sculpture collection of the Royal Academy. Though we cannot be sure

that Baretti is referring to the sculpture on display here, his description

suggests that works like it may have been difficult to categorize even in the

eighteenth century: AFRICUS.

"For want of a better, I give this name to a Head of a

Blackamoor, which is in the Niche of this Room.

A Friend of mine would have it called Boccar, or Boccor, an

African King named in one of Juvenal’s Satires. But, as it has no ensigns of

Royalty about it, I imagine it to be a Portrait of some Slave, if not a

fanciful performance intended to characterise the general Look of the African

faces.

Whatever it be, I think it a fine thing of the kind".

In the nineteenth century, Harwood’s bust was mistakenly

believed to be a portrait of an athlete named Psyche in the service of the

first Duke of Northumberland".

Another version of this sculpture, which bears Harwood’s

signature and the date 1758, is now at the J. Paul Getty Museum.

Text above lifted from the Yale Centre for British Art website

In light of the appearence of the plaster bust it would seem some of this needs to be reappraised

https://www.britishartstudies.ac.uk/index/article-index/bust-of-a-man/issue/issue-1/page/1

http://pdf.britishartstudies.ac.uk/Issues/issue-1.pdf

http://idiscoveredamerica.com/?p=52

http://idiscoveredamerica.com/?p=149

http://idiscoveredamerica.com/?p=292

Photographs of the two busts shown here side by side for

comparison.

The details of the ear make it clear that these busts are of

the same man.

It would seem fairly obvious to me that the detail of the

new scar on the forehead would suggest that the Yale bust is the original and

that the Getty bust is a later version.

The scar on the Yale bust clearly shows the stitch marks

which have healed over in the Getty bust.

the hair on the Yale bust has much deeper drilling and the

curls are much more defined.

The early history and provenance of both of these busts is

unclear.

It has been suggested that the date on the Getty bust has

been recut, but the inscribed signature is close to that on other busts such as

the Sotheby's Caracalla.

The date of 1758 on the Getty busts implies that it was

sculpted in Italy.

_________________________________

Bust of A Man

at the J Paul Getty Museum

http://www.getty.edu/art/collection/objects/1199/francis-harwood-bust-of-a-man-english-1758/?

see also, for a rather verbose article on the two busts:

The surface of this bust has undergone at least one program of restoration - the Getty "conservation work and analysis shows that the bust’s original, eighteenth-century coating was a medium, translucent brown.

In

fact, conservators have in recent years removed much of the thickly applied

black paint, wax, and shellac that had been applied to the bust in the 1980s,

in an attempt to bring the surface colour closer to the varied texture and tone

of the underlying marble".

"With noble bearing, this man proudly holds his chin

high above his powerful chest. Sculptor Francis Harwood chose a black stone to

reproduce the sitter's skin tone. Harwood also chose an unusual antique format

for the bust, terminating it in a wide arc below the man's pectoral muscles.

Harwood was familiar with antique sculptures from time spent in Florence

reproducing and copying them. He may have deliberately used this elegant,

rounded termination, which includes the entire, unclothed chest and shoulders,

to evoke associations with ancient busts of notable men. Although the identity

of the sitter is unknown, the scar on his face suggests that this is a portrait

of a specific individual. This work may be one of the earliest sculpted

portraits of a Black individual by a European".

___________________

Provenance:

1786 - 1817: possibly Hugh Percy, second duke of Northumberland, English, 1742 - 1817, possibly by inheritance to his son, Hugh Percy.

1817 - 1847: possibly Hugh Percy, third duke of Northumberland, English, 1785 - 1847, possibly by inheritance to his brother, Algernon Percy.

1847 - 1865: Algernon Percy, Fourth duke of Northumberland, English, 1792 - 1865 (Stanwick Hall, Yorkshire, England)

Described in the 1865 after-death inventory of

Stanwick Hall as "a fine bust in black marble - W. Richmond the pugilist -

on Italian Marble Plinth."

1865 - 1922

Percy Family, English (Stanwick Hall, Yorkshire, England) [sold, Anderson and Garland, Stanwick Hall, Yorkshire, May (no day), 1922, lot 189] - description of lot 189 as "A Carved Black Marble Bust of a Negro, 27 in. high, by F. Harwood, on circular Sienna marble plinth and wood pedestal, 4ft, high (in the margin in black ink is indicated the amount of 2.10 pounds)

Before 1987 Private Collection (England) [sold, Christie's, London, April 9, 1987, lot 83 to Cyril Humphris]

1987 - 1988 - Cyril Humphris, S.A. (London, England), sold to the J. Paul Getty Museum, 1988.

......................

Of Tangential Relevance -

This dropped into my in box from John Sullivan on 4 Dec 2024.

I thought that this was the most relevant place to save it.