Continuing my investigations into the Life and Works of John Cheere.

Venus and Vulcan

Pair of Marble figures; each signed 'Cheere Fec.' to the base

21 5/8 in. (55 cm.) and 20 ½ in. (52 cm.) high.

These statues had been sold by Messrs Cheffins of Cambridge on 12 February 2004, Lot 474 .

Consigned from Papworth Hall, Cambridgeshire – built in 1809 by Charles Madryll Cheere, who married Sir Henry’s granddaughter and later assumed his name.

The pair are both signed, Vulcan with Cheere Fect and Venus with Cheere Fec.

Both figures had been catalogued as “rather dusty and surface

marked”, and both had some damage, especially Venus, who had suffered a broken

neck and five breaks to her right arm and hair, as well as damage to her left

toes and a crack to her left ankle. Her base also showed damage around the

sides.

Offered by Christie's London 6 July 2023. Lot. 7.

They say in their catalogue entry -

"Almost certainly the marbles offered in the collection of

Sir Robert Ainslie, bart.; Christie's London, 10 March 1809 (but seemingly

offered on behalf of a different vendor, 'Hope'), lots 97 and 98, unsold".

Biographical Dictionary... Yale 2009. states sold for 40 gns.

It is not clear whether they sold at Christie's

https://www.christies.com.cn/en/lot/lot-6436457

It had been assumed that these statues had been carved by Sir Henry Cheere (1703 - 1781), but I would tentatively like to make the case that they were carved by his brother - the until recently the much less well known John Cheere (1709 - 1787) of Hyde Park Corner.

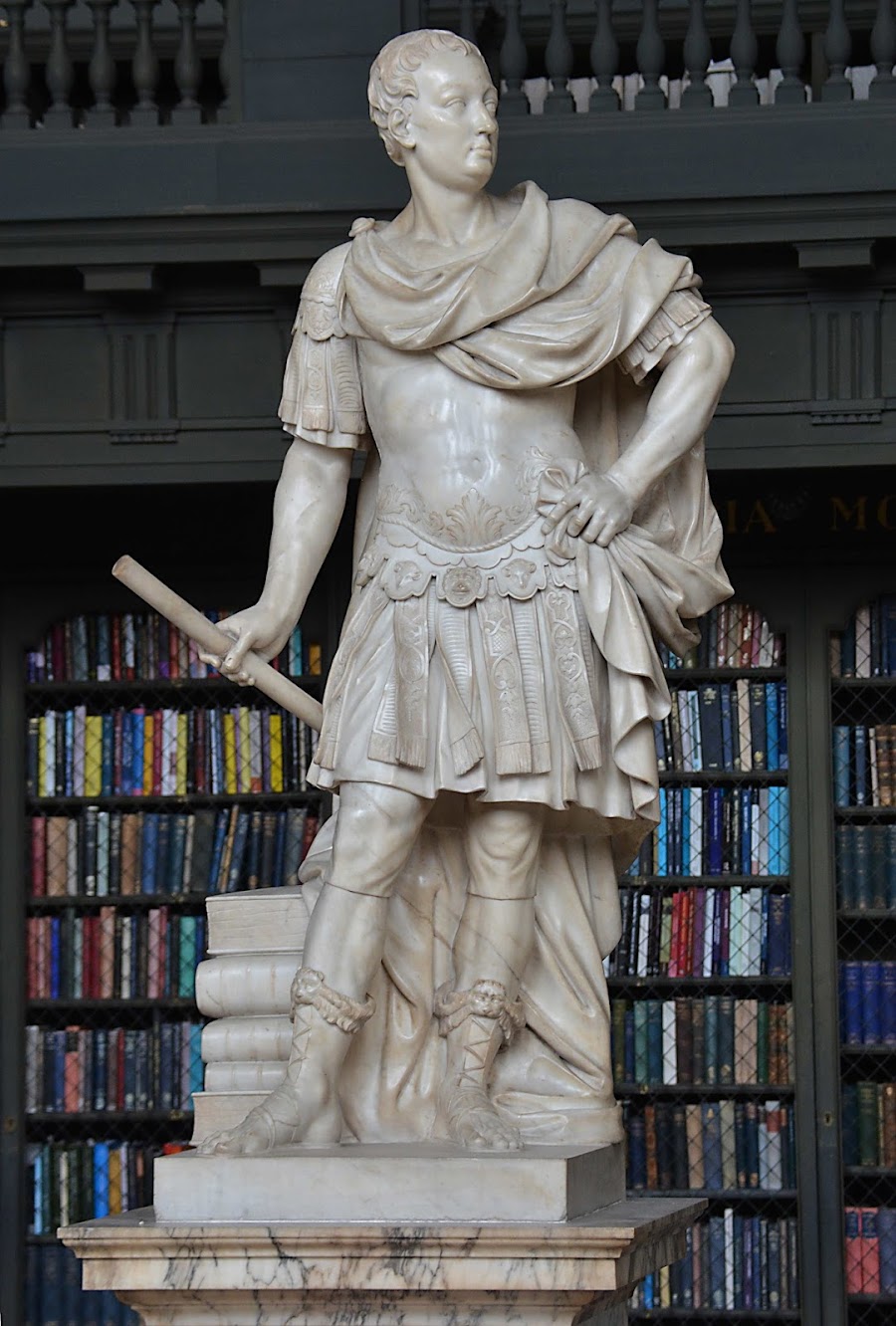

Inscribed H. Cheere. Fecit. Erected in 1734.

Suggested by George Clarke.

In the Former Codrington Library

See for Clarke Cheere and Statuary in Oxford - History of Universities: Volume XXXV / 1: The Unloved Century ..., Volume 35 By Mordechai Feingold

The Statues of Archbishop Sheldon, the Duke of Ormonde, cost £223 7s 10d. (1737 - 38).

were carved by Henry Cheere. Removed 1958-63 due to their

poor condition.

...........................

The gilt lead equestrian statue of the Duke of Cumberland

had been erected in 1770 at the cost of Lt. Gen. William Strode, who had fought

under and befriended the Duke, and whose own memorial in Westminster Abbey

records him as ‘a strenuous assertor of Civil and Religious Liberty’. At the

time Strode lived on Harley Street, on the north-east corner with Queen Anne

Street. The Duke’s sister Amelia, who had paid for a lead statue of George III

for Berkeley Square in 1766, lived at the west end of the north side of

Cavendish Square. Strode conceived what was London’s first outdoor statue of a

soldier in 1769, the same year he was alleged to have withheld clothing from

his soldiers, a charge of which he was acquitted at a court martial in 1772.

The Equestrian Model in the Royal Collection.

Here suggested as by John Cheere.

Acquired by Queen Elizabeth II in 1969, this lead statuette

depicts William Augustus, Duke of Cumberland (1721-1765), and third son of King

George II, on horseback. In 1746, he defeated Charles Edward Stuart - also

known as Bonnie Prince Charlie or The Young Pretender - putting an end to the

Jacobite rebellion in Scotland. The Duke of Cumberland is portrayed wearing a

tricorn hat and a jacket with a stylised garter badge and a sword. Fitted to

the horse trappings are two pistols in holsters. Made circa 1750, this statue

is thought to have been made by the English sculptor Sir Henry Cheere and to be

a reduction of the life-size monument in lead, also made by him, which was

erected in Cavendish Square in 1770 - this monument was pulled down by the Duke

of Portland and melted in 1868.

The Portland Stone Plinth remains in the Square.

COMPARATIVE LITERATURE

M. Whinney, Sculpture in Britain 1530-1830, London, 1992,

pp. 191-197.

T. Friedman and T. Clifford, The Man at Hyde Park Corner -

Sculpture by John Cheere (1709-1787), Leeds, 1974, pp. 3-10.

M. Snodin ed, Rococo: Art and design in Hogarth's England,

exhibition catalogue, London, Victoria and Albert Museum, 1984, pp. 278-309.

T. Clifford, ‘The Plaster Shops of the Rococo and

Neo-Classical era in Britain’, Journal of the History of Collections, IV,

January 1992, pp. 41 and 50.