Post under construction.

Some illustrations and brief notes.

A Book of Designs in Pen and Ink and Watercolours at the Taylorian Institute, Oxford.

Photographed by the author 14 August 2019.

Sir Robert Taylor d. 1788 Part 1.

Apprenticed (aged 18) to Henry Cheere in 1732 for £105.

I am very grateful to staff at the Taylorian Institute for allowing me access and to photograph this group of exquisite drawings.

This is the largest surviving group of drawings by a sculptor in the mid 18th Century.

There is a small group of drawings by Taylors master Henry Cheere at the Victoria and Albert Museum.

There are also several anonymous drawings of monuments at the V and A which can be safely ascribed to Henry Cheere.

see my post -

For a very useful introduction to Taylor see - Binney, Marcus. Sir Robert Taylor : from Rococo to Neoclassicism. London: Allen & Unwin, 1984.

As far as I know no one has attempted an in depth illustrated biography after Binney and I will not attempt to do so here -

The purpose of this website is to illustrate and discuss English sculpture of the 18th century - I will of course touch on the work of Taylor as an architect and property developer but here is not the place to go into great detail - I will leave that to others.

..............................

Taylor at Spring Gardens Charing Cross.

Walpole suggests that the original Spring Garden properties were financed by annuities to two brothers who died within 18 months.

info here from - https://www.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol16/pt1/pp131-135

The St Martin's ratebook for 1746 shows Robert Taylor appearing in a house which in 1757 was merged with the adjoining house to the west to form what was afterwards numbered 34 in Spring Gardens (altered in 1866 to No. 3). In 1778 Taylor purchased the premises from Conyers Dunlop. In the indenture the frontage to Spring Gardens is given as 37 feet 4 inches, and the abuttals are described as north, partly on the freeholds of Robert Taylor, Robert Blount and Sir Henry Cheere and partly on Mermaid Court; west, on the freeholds of Francis Plumer, Robert Taylor and Robert Blunt; and east, on the freehold of Conyers Dunlop and Mermaid Court.

It was perhaps in this house that

Taylor's son Michael Angelo Taylor (fn. n19) was born (fn. n20) in 1757, and

there Taylor (then Sir Robert) died in 1788. His widow continued to

reside at the house until her death in 1803. In 1805 "Dr.

Maton" ( is shown as occupying the house. He resided there for 30

years, dying on 30th March, 1835, "at his house in Spring Gardens,

London."

For an interesting article on speculative building by Henry Cheere and Robert Taylor see -

https://georgiangroup.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/GGJ_2002_13-GARNIER.pdf

Though best remembered as a distinguished architect, Taylor

trained as a sculptor and practised the profession with considerable success

for nearly 30 years. He was born in Woodford, Essex in 1714, the son of Robert

Taylor I. After ‘some common schooling’ (Anecdotes 1937, 192) he was

apprenticed in 1732 to Sir Henry Cheere at a fee of £105. Taylor was still

working for his master in 1736-37, when payments were recorded to the younger

man in Cheere’s account at Hoare’s Bank. To gain ‘more pretension in his profession’

(Farington vol 16, 5744) Taylor travelled to Rome in the early 1740s ‘on a plan

of frugal study’ (Anecdotes 1937, 192), but felt compelled to return home when

he heard that his father had fallen ill. He was unable to get passports because

of the continental wars and so disguised himself as a friar and crossed hostile

territory in the company of a Franciscan monk. He apparently kept his

ecclesiastical apparel as a keepsake until his death.

Taylor’s father died in October 1742, leaving considerable

debts. Although Taylor later told a friend that he had only eighteen pence in

his pocket at the time, he was soon able to set up a thriving sculptural

practice, thanks to hard work and good connections. He received financial help

from the Godfreys of Woodford, a family of distinguished East India Company

merchants to whose memory he later erected a large marble column (34). In the

mid 1740s he took premises in Spring Gardens near the King’s Mews, to the east

of Cheere’s workshop. On 3 August 1744 he became free by patrimony of the

Masons’ Company.

In the same year, despite competition from the more

established sculptors, L F Roubiliac, Peter Scheemakers, Henry Cheere and

Michael Rysbrack, Taylor won the contract to carve the pediment group for the

Mansion House in the City of London (42). Vertue suggested that Taylor (who was

so unfamiliar to the writer that he mistakenly called him ‘Carter’) was chosen

because he was English, a ‘Cittizen & son of a Mason’ (Vertue III, 122).

Taylor executed a large allegorical relief extolling the benefits of trade in

London. In April 1746 the architect George Dance told the Mansion House

committee that the work was ‘very well done’ (CLRO Minutes, quoted in

Ward-Jackson 2003, 242). Interpretations of the iconography appeared in the

London Magazine and the Gentleman’s Magazine.

In 1747 Taylor was chosen, apparently without a competition,

to carve the monument in Westminster Abbey to Captain Cornewall, a victim of

the Battle of Toulon (22). This monument was the first in the Abbey to a war

hero financed with parliamentary funds and was intended to salvage some glory

from a battle which had resulted in two court-martials. The design, depicting

Fame and Britannia on either side of a palm tree above a rocky base, was felt

by a French critic, Grosley, to be closer in spirit to the magnificence of a

pompe célebre than a standing monument (Grosley 1772, vol 2, 67). When it was

unveiled in February 1755, The Gentleman’s Magazine, less-concerned with its

iconographical qualities than its political significance, called it an

‘illustrious instance of national gratitude as well as of good policy’ (GM, vol

25, 89).

Taylor’s other Abbey monument, to Joshua Guest (17) was

considered by Horace Walpole to be his finest memorial (Anecdotes 1937, 193)

and Vertue praised the work, adding that the ornaments and the multicoloured

marbles had brought Taylor some reputation. Vertue added that Taylor had

‘infinitely polishd his work beyond comparison this being another English

artist who made the tour of Italy’ (Vertue, III, 161). In his church monuments

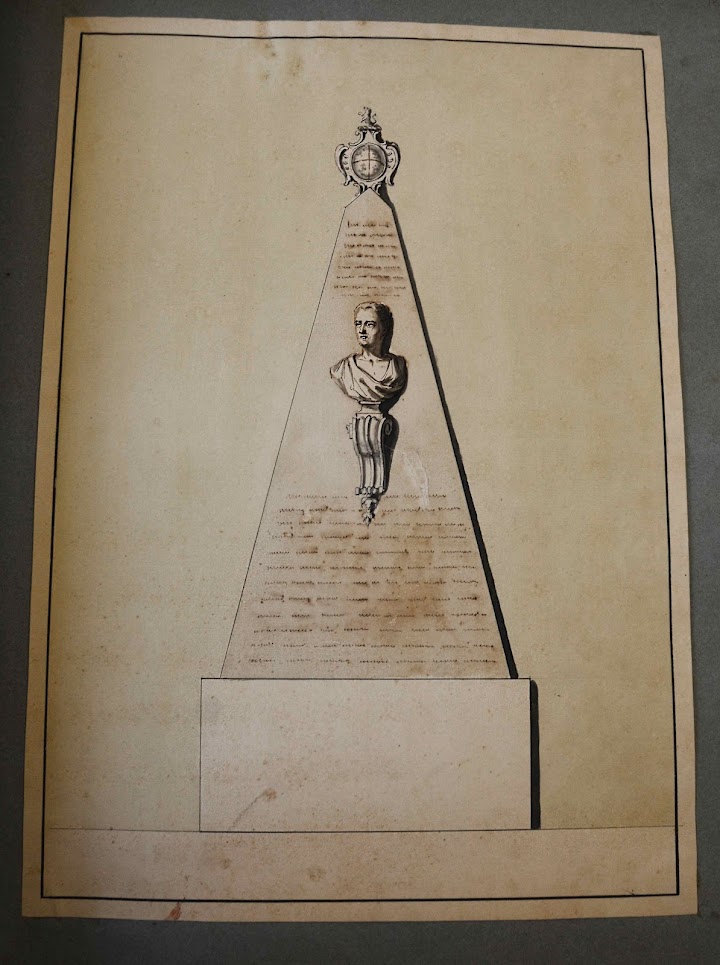

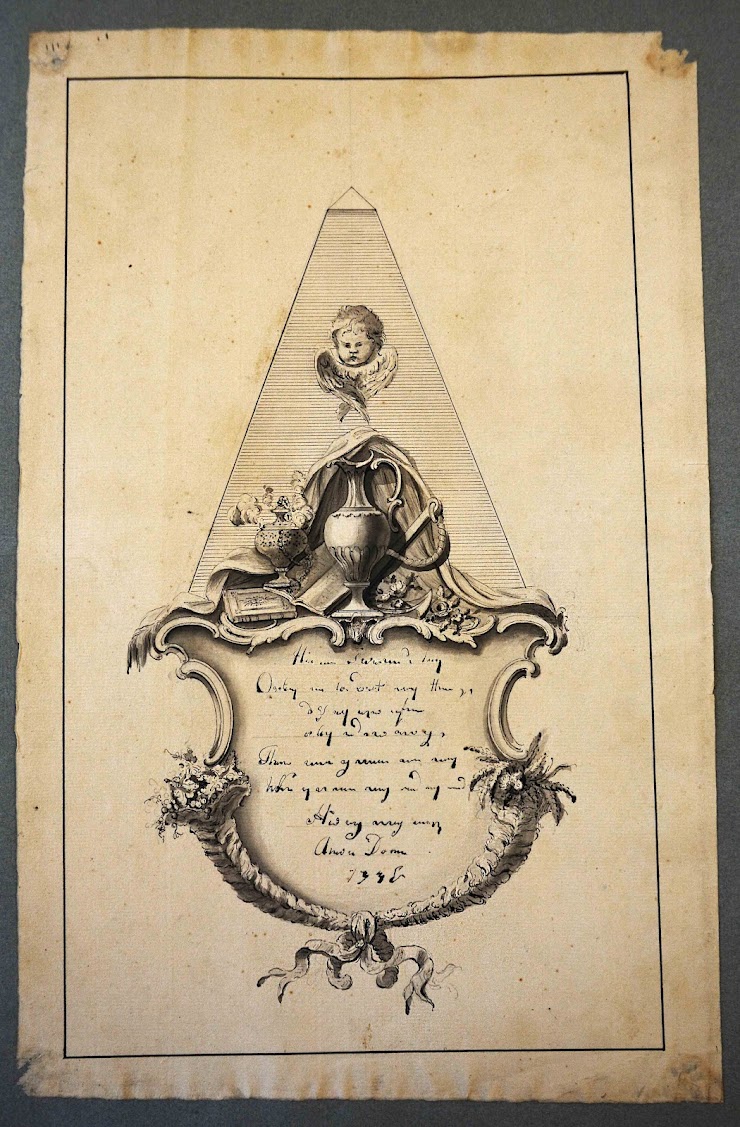

Taylor developed an innovative and distinctive vocabulary of motifs: he presented

portrait busts en negligé (4, 6, 19), and made use of medallion portraits (29,

30), praying putti precariously placed on a pedestals (21, 25, 31) and one

almost grotesque weeping widow (15). The monuments often incorporated

polychrome marbles (17, 19) and were framed with floral rococo ornaments (11,

12, 16), oak sprigs (21), crossed palm branches (21, 27, 28, 30), and egg and

dart carving (20, 26). Taylor may well have repeated these designs. There are

several more unsigned works in the British Isles and the former colonies which

closely resemble these signed works or else Taylor’s surviving drawings. His

most ambitious design was for the monument to Henry, Earl of Shelburne at High

Wycombe, a multi-figured baroque fantasy which drew heavily on modern Roman

models. This was rejected in favour of a design by Peter Scheemakers but Taylor

was paid £20 for his trouble. In addition to the identified works he is

credited with the monument to Thomas and Robert Crosse, c1745, at Nettleswell,

Essex and to John, Lord Somers, †1716, at North Mymms, Herts (Baker 2000, 51-2,

57, 60, 172 n33, repr; Bilbey 2002, 157, repr).

The executed works rarely match the designs in quality and

Walpole hinted at one good reason: Taylor’s method ‘was to bost, as they call

it, to hew out his heads from the block; and except some few finishing touches,

to leave the rest to his workmen’ (Anecdotes 1937, 193). Bartholomew Cheney is

his only identified assistant: Smith remembered that Cheney was paid £4 15s a

week for carving the figures on the Cornewall monument (Smith 1828, vol 1,

151).

Taylor produced some remarkable ‘Chinese Chippendale’

designs for chimneypieces, a book of which survives at the Taylorian Institute,

Oxford. These reproduce in multiple form the floral motifs used on his

monuments. In 1750 he supplied a chimneypiece for the London house of Peter Du

Cane, a Director of the Bank of England and the East India Company (38) as part

of a larger project of building and renovation, and this is Taylor’s first

datable architectural work. Taylor still described himself as a ‘statuary’ in

1758 (Survey of London, vol 29, 141), and he continued to produce monuments

until the late 1760s, but his business moved steadily into the field of

architecture.

Working chiefly for a City clientele of bankers, East and

West Indian merchants, government financiers and lawyers, Taylor became one of

the two leading architects of his day. Thomas Hardwick wrote that before Robert

Adam entered the lists, Taylor and James Paine ‘nearly divided the profession

between them’ (Hardwick 1825, 13). Taylor’s architecture, like his sculptural

work, made use of recurring elements, such as astylar elevations, vermiculated

rustication, cantilevered staircases and rich rococo chimneypieces. His

particular strength lay in his designs for compact houses for rich city

dwellers and he is often credited with moving the Palladian style towards

neoclassicism. His only major public building was the Bank of England

(1765-87), now demolished. Walpole said Taylor was responsible for the statue

of Britannia, pouring coins from a cornucopia, which survives on the pediment

of one of the current buildings. This claim is brought into question by a press

report of 1733 which records that the commission was originally given to Sir

Henry Cheere.

By 1768 Taylor had amassed a fortune of £40,000 and his

professional income was £8,000 a year. This is a remarkable achievement,

bearing in mind that his first £15,000 was used to clear family debts. At the

time of his death he was said to be worth £180,000. Much of this wealth came

from his position as surveyor of several London estates, including the Duke of

Grafton’s. He was surveyor to the Bank of England, the Admiralty, the Foundling

Hospital, Greenwich Hospital and Lincoln's Inn. He also held a number of posts

in the Office of Works. In 1782 he was knighted, on the occasion of his

election as Sheriff of London.

Contemporary sources construct Taylor as a paragon of

stoical and devout professionalism. He ate little meat, abstained from alcohol,

devoted all his evenings to his wife and a handful of sensible friends, and

rarely slept beyond four in the morning. According to Farington he had three

rules for growing rich ‘viz; rising early, - keeping appointments, - and

regular accounts’ (Farington vol 3, 841). He was said to be attentive to his

pupils, and he trained many of the most successful architects of the next generation,

notably Samuel Pepys Cockerell and John Nash.

Taylor died on 27 September 1788 at the home in Spring

Gardens, London which he had built in 1759. He fell ill after attending the

funeral of his friend, the banker and one-time Lord Mayor, Sir Charles Asgill,

and died a few days later of a ‘violent mortification in the bowels’ (Anecdotes

1937, 197). After a grandiose funeral attended by over a hundred people, Taylor

was laid to rest in a vault near the north-east corner of St

Martin-in-the-Fields. The bulk of his fortune was left to the University of Oxford

to found an institution for the teaching of modern languages. His will was

challenged by Taylor’s son, Michel Angelo Taylor MP, but after his death in

1834 the Taylorian Institute was founded in accordance with Taylor’s wishes. It

houses Taylor’s library of architectural books and two volumes of his drawings.

Michel Angelo Taylor later commissioned Thomas Malton the Younger to draw and

engrave a set of 32 plates of his father’s architectural designs (1790-2, SJSM,

Ashmolean).

A cenotaph was erected in Poets’ Corner, Westminster Abbey

asserting that Taylor’s ‘works entitle him to a distinguished rank in the first

Class of British architects.’ This verdict has been endorsed by later

architectural historians but much less attention has been given to his

achievement as a sculptor. Whinney dismissed Taylor’s oeuvre as ‘clumsy’ and

‘foolish,’ but her view fails to do justice to the Cornewall and Mansion House

commissions, nor does it take into account the innovative nature of Taylor’s

monumental designs. Baker has drawn attention to Taylor’s assimilation of

continental influences from the works of Gille-Marie Oppenard (1672-1742),

Juste Aurele Meissonnier (1695-1750) and Sebastien-Antoine Slodtz (1695-1754),

and has concluded that Taylor was one of the three major artists, who, with Sir

Henry Cheere and Roubiliac, evolved the rococo style in English sculpture (

Rococo 1984, 282-3) .

MGS

Literary References: Vertue, III, 122, 161; GM, vol 18, pt

2, 1788, 930-1, reproduced with other obituaries of Taylor in Anecdotes 1937,

191-198; Hardwick 1825, 13; Smith 1828, I, 151; Builder 1846, no194, 505;

Esdaile 1948 (1), 63-6; Survey of London, vol 29, 141; Gilson 1975; Farington,

passim; Summerson 1980, 2-5; Rococo 1984, 277-309; Binney 1984; Whinney 1988,

248-9; Colvin 1995, 962-7; Grove 30, 1996 385-7 (White); Coutu 1997, 79, 85;

Craske 2000 (2), 106; Ward-Jackson 2003, 239-41; ODNB (Baker)

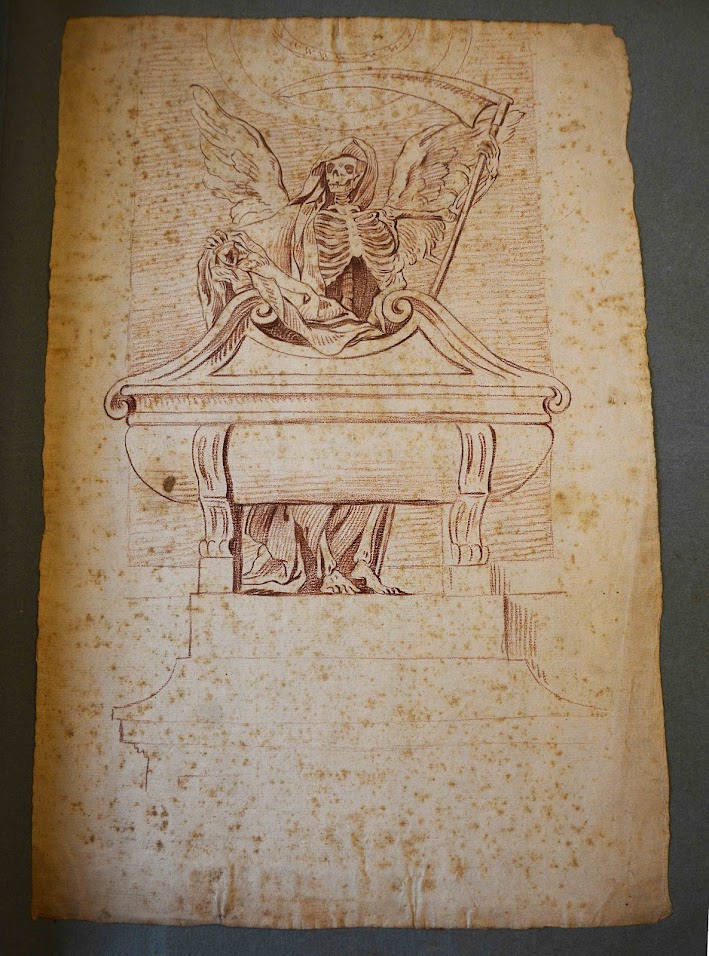

Collections of Drawings: TI (Arch Tay 1), book of 54

designs, 52 of which are for monuments, pen, pencil, chalk, ink and wash,

Rococo 1984, 297-298, 308 (repr), Baker 2000, 65 (repr), Garstang 2003, 853

(repr), photos of about 50 of these drawings, Conway; TI (Arch Tay 2) 12,

highly finished designs for chimneypieces, pen, ink and wash, Binney 1984,

reprs 59-62, Esdaile 1948 (1), 66 (repr), C Lib (repr); TI (Arch Tay 3), a book

of ‘Problems in Geometry and Mensuration with Diagrams,’ red and black ink.

Portraits of the Sculptor: Anon (possibly William Miller),

half length portrait, RIBA, Binney 1984, repr 1; Anon, half length portrait, TI

(similar to that in RIBA)

He was the father of the sculptor-architect Sir Robert

Taylor (1714-1788) and a successful master mason and monumental sculptor in his

own right. The son of a yeoman from Campden, Taylor was apprenticed to the

mason Richard Garbut on 6 December 1705, and became free of the Masons’ Company

on 2 October 1712. He was master of the Company in 1733 and clearly took his

civic responsibilities seriously for he became a captain in the City’s trained

bands. In 1723 he subscribed to John Dart’s Westmonasterium as ‘Mr R. T.,

Mason, in Greyfriars’ and in 1726 enodorsed Dart’s History of the Cathedral

Church of Canterbury in like manner.

Taylor worked for several of the City Livery Companies. He

was paid £19 7s for unspecified masonry, commissioned by the Ironmongers’

Company in 1722, and his work for Masons’ Hall included a chimneypiece (15). He

received £69 from the Grocers’ Company for decorative carving undertaken in

1735-l736 (18) and Gunnis suggests that he acted as master-mason for the Barber

Surgeons when their theatre was rebuilt to designs by Lord Burlington. From

1725-39 he was mason for the Royal College of Physicians and he was also

responsible for a good deal of building work at St Bartholomew’s Hospital,

1728-40 (14, 16). In 1728 he rented two tenements in Duck Lane from the

governors of the latter Hospital. When the contract to build the London Mansion

House went to tender on 16 May 1738 Taylor, Christopher Horsnaile II and a

haberdasher, John Townsend, competed with a rival team of masons headed by

Thomas Dunn and John Devall. After much jockeying all five shared the contract,

providing obelisks, plinths and paving in addition to structural work.

Records of Taylor’s contribution to domestic buildings are

scant but the Hoare partnership ledgers record a chimneypiece supplied to

Stourhead in 1724 (13). In 1732 he received a further £150 for unidentified

work at Stourhead and in 1733 another £98. Gunnis thinks these payments were

probably for chimneypieces, but tentatively suggests that Taylor may have had

something to do with the building of Alfred’s Tower in the grounds, or with the

carving of King Alfred’s statue.

Taylor was responsible for a number of elaborate, if

repetitive, monuments in which he made use of a range of coloured marbles. The

Kidder (1) has a reclining female in a skimpy shift gesturing towards the plain

slab behind her, which is framed by a curtain, winged cherubs’ heads and

sunbeams within composite columns. The Askel (2) is a wall monument with

pilasters, flaming lamps, and cherubs at either side, one clasping a skull.

Gunnis considers the Deacon (7) his best work and Whinney notes that it is in the

manner of Francis Bird. It has a reclining effigy in contemporary dress, with a

baroque flourish to the draperies covering the lower body. Deacon again

gestures at the inscription slab behind him and he clasps a skull in the other

hand. The Corinthian frame is decorated with heads of putti backed by clouds,

and sunbeams slant through. The Raymond (4) is an architectural wall-tablet

with an armorial shield and winged cherub-heads on the apron, and the Napier

(9) uses a similar vocabulary of ornaments, but includes two stocky females on

either side of the architectural frame. The Chester (12) is a little different,

for it has a relief panel of Chester’s widow and children above the inscription

tablet. The classical pilasters are flanked by seated cherubs and two boys sit

at the bottom of the slab on the gadrooned base. All the figures gesticulate

dramatically.

The names of several apprentices are listed in the archives

of the Masons’ Company. John Percy joined him in 1715, Francis Cunningham in

1722 and John Mallcott in 1730. Charles, ‘son of Robert Taylor of Christchurch,

London, Mason’ was apprenticed on 23 June 1737 to Thomas Fletcher of Chipping

Campden.

The obituary, written by Horace Walpole in the Gentleman’s Magazine of the son, Sir Robert Taylor, notes -

‘His father was the great stone-mason of his time; like Devall in the present day he got a vast deal of money; but again, unlike him altogether, he could not keep what he got. When life was less gaudy than it is now, and when the elegant indulgences of it were rare, old Taylor the mason enjoyed them all. He revelled at a villa in Essex; and as a villa is imperfect without a coach, he thought it necessary to have that too. To drive on thus, at a good rate, is generally thought pretty pleasant by most men; but it is not apt to be pleasant to their heirs.

It was so here.

For excepting some common schooling; a fee, when he went pupil to Sir Henry

Cheere, and just enough money to travel on a plan of frugal study to Rome,

Robert Taylor got nothing from his father.’ (Anecdotes 1937, 192). (Add inf,

AL/RG)

IR/MGS

Literary References: Webb (3), 1957, 116; Gunnis 1968, 381;

Whinney 1988, 248-9; Jeffery 1993, 49-50, 67-8, 297, 300; Colvin 1995, 962;

Webb 1999, 9, 19, 21, 25, 32

Archival References: Ironmongers, WA, vol 10, fol 19;

Masons’ Co, Freemen, fol 68; Masons’ Co, Court Book, 1705; Court Book, 1722-51

(29 Oct 1742); Apprenticeship Lists, 1737; Charles Taylor, Hoare partnership

ledger, 1725-34, 1725-34, fol 272, 22 Dec 1732 (£150); fol 282, 4 July 1733,

Joseph Cox’s bill to Robert Taylor (£98).

..............................

A Monument to Jane Brewer by Robert Taylor Senior.

Robert Taylor I (1688 - 1745).

1716.

West Farleigh, Kent.

Born about 1688, Taylor was apprenticed to Richard Garbut, and became free in 1712. He was much employed on carving statues, monuments, and chimney pieces, and was mason to several of the City Companies.

He was also patronized by Sir Richard Hoare, the banker, carving mantlepieces and garden statuary for Stourhead.

He made a large fortune out of his business, but wasted it by living extravagantly at a house he bought in Essex.

His monumental masterpiece is the reclining figure of Thomas Deacon, 1721, in Peterborough Cathedral. He was the father of Sir Robert Taylor, the architect and sculptor.

Info here from - Signed Monuments in Kentish Churches by Rupert Gunnis.

available on line at -

This post-in-progress already offers fascinating historical context! Your notes on Sir Robert Taylor’s apprenticeship under Henry Cheere and the detailed references to his Spring Gardens residence provide a strong foundation. The inclusion of primary sources and scholarly references like Binney and the British History Online entry adds great academic value—readers interested in 18th-century English sculpture will appreciate the depth and precision you bring to this topic.

ReplyDelete